The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes (trans. by W. S. Merwin; intro. by Juan Goytisolo). New York: New York Review of Books, 2005.

In the Spanish novella The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes, Lazaro tells the story of his life, or rather unwinds the string of “fortunes and adversities” he experienced in the service of a series of difficult masters. He is the picaro, and the genre which his story inaugurated is the picaresque. Authorship is unknown but the book was published in Spain and the Netherlands in 1554. Satirizing certain church figures and their abuses, it was banned and listed by the Inquisition. Here is one of its early title pages, from Burgos.

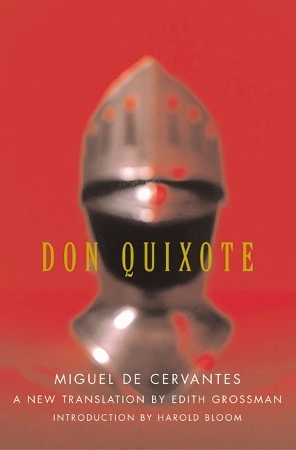

Lazaro’s story runs only 118 pages in poet W. S. Merwin’s adept 1962 translation; in one or two delectable gulps, one can easily digest a work that is rewarding in itself and also one of the major precursors of Don Quixote. Lazaro’s parents were often in trouble themselves, so the boy had to leave his mother’s home early and manage as best he could as the servant of a blind beggar. This man beat him and taught him how to survive in a world that only seemed to offer similar treatment whatever the station of those doling it out. After barely escaping this first master with his life, he serves, in turn, a priest, a squire, a friar, a seller of indulgences (also known as a pardoner), a chaplain, and a constable. His third master, the squire, is the kindest and also the most important in terms of the story’s legacy for literature.

The squire is a penniless and starving nobleman and, as his servant, Lazaro covers for his master’s down-at-heels condition and begs door-to-door to obtain food for them both. In their conversations, we have the germ of Don Quixote and Sancho, the impractical hidalgo and his more sensible companion.

“Lazaro, it’s late, … Let’s get along as best we can, and tomorrow, once the daylight is here, God will be good to us. I’m all by myself so I hadn’t got anything laid in; I’ve been eating out for the last three days. But now we’ll have to make other arrangements.”

“Oh, as for me, sir,” I said, “set your mind at rest. I’m capable of going without food for a night, or even longer if necessary.”

“You’ll live longer and keep your health better,” he answered. “Because as we were saying, there’s nothing in the world like eating little to make you live long.”

“If that’s the way of it,” I said to myself, “I’ll live forever, because I’ve kept that rule religiously, and for that matter I expect I’ll have the bad luck to keep it for the rest of my life.” (The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes, pp. 62-63)

But whereas Lazaro moves on alone, to suffer more mishaps with new employers, Cervantes makes his pair of Don Quixote and Sancho undergo most adventures as a unit, confronting the villains and tricksters they meet on the road as a team.

Don Quixote is not a picaresque novel, nor is its hero a picaro, any more than it is a straightforward chivalric romance, the other genre that Alonso Quexana addled his brains with and Cervantes used, parodied, and transformed. Cervantes’ novel expands and defies genre; it is too self-conscious for romance and too subtle in conception for picaresque. Lazarillo de Tormes is specifically mentioned in chapter XXII of the First Part of Don Quixote, by Gines de Pasamonte, one of the chain gang of galley slaves that Don Quixote has freed. Gines announces that he is writing The Life of Gines de Pasamonte, and brags that, “It is so good, that it’s too bad for Lazarillo de Tormes and all other books of that genre that have been or will be written” (Don Quixote, trans. Edith Grossman, p. 169).

If the list of Lazaro’s masters reminds you of Chaucer’s Canterbury pilgrims, this is no accident, since Lazarillo de Tormes represents a link between medieval tales and the novels which were soon to follow, beginning with Don Quixote. As Juan Goytisolo points out in his Introduction to Lazarillo, Lazaro learns and changes over the course of his adventures, unlike the protagonists of medieval tales who tended to illustrate fixed traits (e.g., patient Griselda).

Don Quixote is often cited, quite rightly, as an important influence on Mark Twain, but Twain’s greatest work also bears comparison with Lazarillo. Huckleberry Finn tells his story in the first person, as Lazaro does, and Huck is closer to the hungry, penniless boy Lazaro than to the courtly, lovestruck Don. However, when Huck joins forces with Jim, their partnership both pays tribute to Cervantes’ immortal duo and gives new dimension to the pairing of unfortunate heroes.

- Don Quixote ranks third on The Fictional 100.

Recent Comments