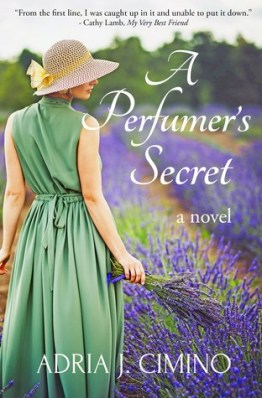

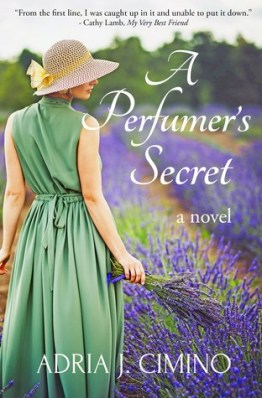

I thank Adria J. Cimino and Velvet Morning Press for the opportunity to review this new novel by Adria, who is already familiar to readers as the author of Amazon best-seller Paris, Rue des Martyrs and Close to Destiny.

My Review

A Perfumer’s Secret is richly evocative of a very special art, the art of composing fragrances, practiced well by only a very few, remarkable people. I’ve never read a story so thoroughly drenched in fragrances–one in which olfactory imagery was not merely added to color and deepen the reality of the fictional world but in which particular scents were themselves central to the plot and keys to character. Scents function as the engine of the plot, and characters are so sensitive to smells of all kinds in their environment that they truly earn the perfumers’ nickname for one of their best: a “nose,” un nez.

Being a nose is a gift, a natural endowment as valuable to their craft as winning the lottery would be to a person deep in debt. And that gift in turn puts them in debt to the world, as they seem to be driven from within to create the most meaningful, memorable scents, which others are then privileged to experience. But to most of us, these nuanced scents and their creators remain a mystery.

The book opens with a haunting prologue:

Zoe Flore’s first creation was the scent of tears. A hot, salty fragrance that she concocted the day her mother died. A perfume built on oak moss, a touch of geranium and the real tears that tumbled into the mix. It was her fifteenth birthday, and from that moment on, she wore the scent as a suit of armor.

Zoe Flore, now 30, is one of these gifted people, a “nose,” who could transform her grief into a living epitaph for her mother, whose memory still infused her consciousness and her creative life. As Zoe works on new fragrance ideas for an important contract, it is her mother’s very particular gift for perfume concoction that occupies her dreams:

she dreamed of her mother composing a fragrance, like the conductor of an orchestra. Barbara Rose sat before the rows of vials, each containing a different basic material. With careful, flowing movements, she went through the routine: selecting vials from the perfume organ, sniffing scent dips that she inserted into one tube and waved delicately over another, then noting each element on a piece of parchment paper. Zoe squinted, but she couldn’t read the words Barbara Rose had printed on the paper.

She awoke in sad frustration. When Zoe thought of her deepest yearnings, it was not, in fact, romantic love she wanted most but “the thrill, the excitement that came with creating an unusual fragrance of unprecedented complexity.”

Unexpectedly, the death of her great aunt Marie-Odile in France broke open the lingering sadness in her life and sent her on a quest to discover her mother’s secrets and her own identity. For one thing, she never knew that her mother, Barbara Rose Flore, was really Barbara Rose Flore-Fontaine, daughter to one of the great families of French perfume makers in the commune of Grasse. Her mother had fled this family, moved to America, and hidden this connection. Zoe was summoned to the reading of her great-aunt’s will where she would inherit a letter, something of incomparable value to her. The scent of the envelope itself told her its origin: it still carried the elusive, but unmistakable scent of Barbara Rose’s perfume, a fragrance she always wore and which Zoe would never forget. The enclosed letter detailed this perfume’s secret formula.

Such a secret was valuable to a host of people beside Zoe, and it only took a short time before the letter was stolen from Zoe’s belongings. Yet, it was still possible she could reconstruct it from memory with a little trial and error.

She decided to stay in France, despite the deadline pressure from her New York City office; they wanted her to take the first plane home and turn in some sort of perfume proposal right away in hopes of pulling off a miracle and securing the coveted contract. But Zoe knew her best chance of recreating her mother’s perfume was right there in Grasse, near her family’s home. Furthermore, she felt inspired to try creating something entirely new and uniquely her own. She rented a picturesque cottage called the Rose of May, frequented by visiting perfumers from around the world. This was her first view of it:

Her eyes drank in the hillsides with their emerald-colored foliage and houses like droplets of rose, violet and mustard. She could almost see through this to the vast flower fields whose perfume drifted delicately into town whenever the wind took hold. How many times had her mother looked out a similar window right here in Grasse?

Grasse is situated at the southeast corner of France on the French Riviera. The painter Fragonard was born here, and Édith Piaf spent her last days here in her villa. With its warm coastal climate, sheltered from salty sea air, it is the perfect farmland for flowers in the many hundreds of species. The profusion of flowers and other plants fostered in Grasse made it the “perfume capital of the world” by the 18th century, a magnet for those who wish to combine the essences of its unique botanical treasures.

Photograph of the Fragonard’s Museum building.

This lush scene is outside the Fragonard Musée du Parfum, adjacent to the Fragonard Perfumerie, one of the few perfumeries that gives public tours. It gives an idea of the beauty of Grasse and why Zoe wanted to stay! The lovely cover of Adria’s book, with its lavender fields stretching toward the horizon, also conjures up the romance of the place, the sheer abundance of it.

Zoe was not working in a vacuum. The family she suddenly acquired already had a heap of their own issues and complications. Some of them were very unhappy about her arrival on the scene, and others proved to be surprising allies. They were vying for that same perfume contract, and they desperately wanted to learn her mother’s secrets too. One competitor in particular, Philippe Chevrefeuille, was a particular problem for Zoe because he captivated her romantically in a way she thought she was immune to. Likewise, he was unnerved by her “scent of tears,” and waivered between wanting to market it as his own and wanting simply to drink it in and discover the reasons behind her sadness.

Besides coping with the confusing distraction of Philippe in her life, Zoe had to figure out who took her mother’s formula! Perhaps a greater mystery, what were the circumstances of her creating it in the first place? Why did she leave her family behind so completely when she seemed perfectly suited to the career she was born to?

I won’t hint at the answers to these mysteries, since Adria discloses the truth so deftly as she spins her tale. I will say that I felt I knew Zoe very well as I was reading. I could predict her reactions. Just one example: When she picked up her key for the Rose of May cottage, she declined to have the rental agent show her around. Although the author didn’t say so, I surmised that Zoe didn’t want anyone else’s scents to mingle with her first impressions of the place, the accumulated traces of those perfumers who had lived and worked there. I can only imagine what it must be like to live so deeply immersed in one’s olfactory sense. Or rather, I can imagine it much better now, for having read A Perfumer’s Secret. For me, the title now has a double meaning: the family secret (or secrets) of various characters in this particular story, and the private world of the extraordinary creative people who make original perfumes.

Synopsis

The quest for a stolen perfume formula awakens passion, rivalry and family secrets in the fragrant flower fields of the South of France…

Perfumer Zoe Flore travels to Grasse, perfume capital of the world, to collect a formula: her inheritance from the family she never knew existed. The scent matches the one worn by her mother, who passed away when Zoe was a teenager. Zoe, competing to create a new fragrance for a prestigious designer, believes this scent could win the contract—and lead her to the reason her mother fled Grasse for New York City.

Before Zoe can discover the truth, the formula is stolen. And she’s not the only one looking for it. So is Loulou, her rebellious teenage cousin; Philippe, her alluring competitor for the fragrance contract; and a third person who never wanted the formula to slip into the public in the first place.

The pursuit transforms into a journey of self-discovery as each struggles to understand the complexities of love, the force of pride, and the meaning of family.

Contemporary/ Literary fiction, Women’s fiction

About the Author

Adria J. Cimino is the author of Amazon Best-Selling novel Paris, Rue des Martyrs and Close to Destiny, as well as The Creepshow (release April 2016) and A Perfumer’s Secret (release May 2016).

Adria J. Cimino is the author of Amazon Best-Selling novel Paris, Rue des Martyrs and Close to Destiny, as well as The Creepshow (release April 2016) and A Perfumer’s Secret (release May 2016).

She also co-founded boutique publishing house Velvet Morning Press. Prior to jumping into the publishing world full time, she spent more than a decade as a journalist at news organizations including The AP and Bloomberg News. Adria is a member of Tall Poppy Writers, which unites bright authors with smart readers. Adria writes about her real-life adventures at AdriaJCimino.com and on Twitter @Adria_in_Paris.

Twitter | Facebook | Website | Blog

*******

*Note*: I received an advance electronic copy of this book, in exchange for an honest review. I did not receive any other compensation, and the views expressed in my review are my own opinions.

Tags: Book Reviews, Contemporary Fiction, France, Perfume, Travel the World in Books

Recent Comments